It’s fascinating how some people thrive on certain diets while others struggle, even when eating the same foods? The answer might be hidden in your genes. Nutrigenomics of vitamin metabolism tells how your body processes essential nutrients like B vitamins, vitamin D, and more.

Your genetic makeup plays a bigger role in your health than you might think. Tiny genetic variations, called SNPs, can influence how efficiently you absorb, metabolize, and use vitamins. For instance, a single gene could determine whether your body struggles to process folate or if you’re prone to vitamin D deficiencies. These insights are transforming the way we understand nutrition and opening the door to personalized health strategies. Let’s jump into the science of vitamin metabolism and nutrigenomics.

Key Takeaways

Nutrigenomics bridges nutrition and genetics, revealing how your DNA influences vitamin metabolism and dietary needs.

Genetic variations like SNPs impact vitamin processing, affecting absorption, activation, and utilization of key nutrients like B vitamins, vitamin D, and folate.

Key genes such as MTHFR, CYP2R1, and TCN2 play critical roles, determining individual risks for deficiencies and influencing health outcomes.

Personalized nutrition strategies optimize health outcomes, using genetic insights to tailor vitamin intake and overcome metabolism challenges.

Standard RDAs may not suit everyone, as genetic differences highlight the need for precision in dietary interventions and supplementation.

Integrating nutrigenomics and functional lab testing into clinical practice empowers practitioners, providing actionable data to deliver targeted, effective nutritional interventions.

Table of Contents

Understanding Vitamin Metabolism Nutrigenomics

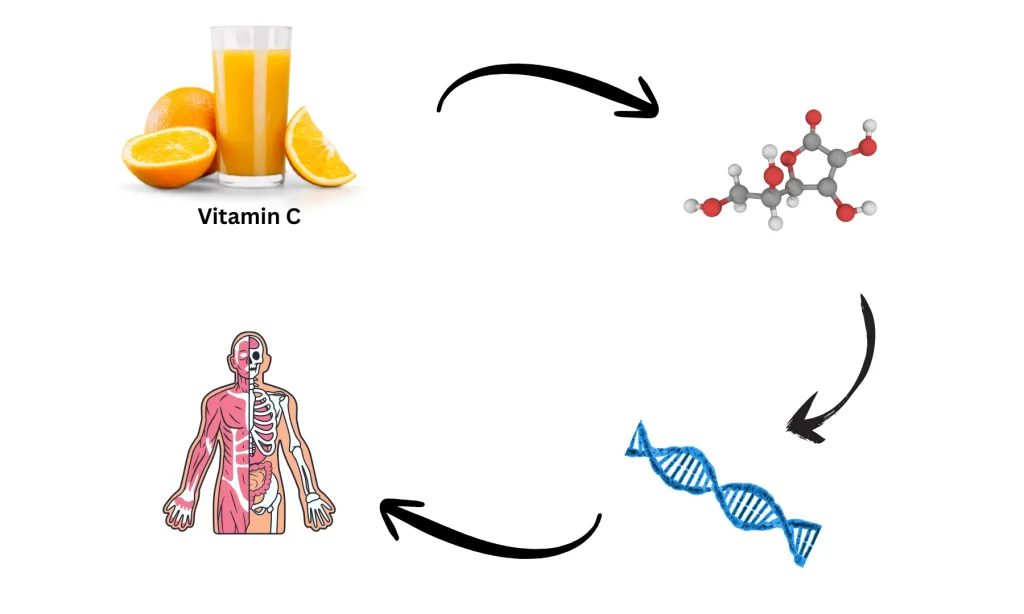

Vitamin metabolism shows how your genes play a key role in how your body processes essential vitamins. Nutrigenomics opens the door to understanding why your body might thrive on one diet while your best friend’s body needs something completely different.

Genetic Variability and Vitamin Absorption

Not all of us metabolize vitamins the same way, and genetic differences, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), are the reason why. These little tweaks can impact how well your body absorbs, activates, or uses vitamins like B12, D, or folate. For example, if you’ve inherited specific SNPs in the MTHFR gene, you might struggle to convert folate into its active form. Without intervention, this could lead to fatigue or other health challenges.

Practitioners can use your unique SNP blueprint to create tailored nutritional strategies. It’s a world apart from the generic Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) you might see on a multivitamin bottle. Basically, it’s nutrition designed for you.

Key Genes That Affect Vitamin Metabolism

Some genes play a major role in how your body processes vitamins.

Vitamin D (CYP2R1 gene):

This gene influences how efficiently vitamin D is converted and utilized. Some individuals may require higher doses to maintain adequate levels.Vitamin B6 (NBPF3 gene):

Variants in this gene can reduce circulating vitamin B6, increasing the risk of deficiency without careful monitoring.

For practitioners, identifying these genetic markers provides a roadmap for clinical decision-making. It supports targeted nutrition strategies and helps prevent chronic conditions associated with nutrient imbalances, including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Personalized Nutrition as a Game-Changer

By applying tools from nutrition genomics, practitioners can align dietary vitamin impact with each patient’s unique genetic profile. The goal is not to overload with supplements, but to understand why specific vitamins may be poorly absorbed or metabolized due to genetic factors, thereby promoting overall hormonal balance through optimized methylation and detoxification pathways.

For example, genetic testing can reveal variations affecting vitamin B12 metabolism, such as MTHFR polymorphisms. Instead of defaulting to higher doses, practitioners may recommend a methylated form of B12, which is more bioavailable for individuals with certain variants and supports efficient estrogen clearance to mitigate risks of estrogen dominance.

This approach enables targeted interventions, reduces trial-and-error in treatment planning, and ultimately supports improved outcomes while helping patients avoid unnecessary costs and ineffective supplementation strategies.

Why This Matters in Clinical Practice

Applying nutrigenomics in practice is straightforward and highly actionable. For dietitians, naturopaths, and other healthcare professionals, understanding a patient’s genetic vitamin metabolism allows you to move beyond generalized nutrition guidelines. Interventions become more precise such as knowing whether a patient truly requires higher doses of vitamin D based on genetic data rather than relying on trial and error.

For practitioners, this shift represents more than convenience—it provides a framework for addressing the root causes of nutrient-related health issues. By integrating genetic insights into care, you can transition patients from reactive treatment models to preventive, personalized wellness strategies that deliver measurable improvements in outcomes.

Genetic Foundations of Vitamin Metabolism

Differences in how individuals respond to the same diet are often explained by genetics. DNA determines how vitamins are absorbed, metabolized, and utilized, making vitamin needs highly individualized.

Key Genetic Variants in Vitamin Utilization

Folate metabolism (MTHFR, MTRR, DHFR):

Variants in MTHFR can reduce conversion of folate into its active form, impairing methylation pathways and increasing risk of deficiency. MTRR and DHFR variants can further reduce efficiency of folate cycling.Vitamin D metabolism (VDR, CYP2R1, CYP27B1, GC):

VDR variants may alter receptor binding, while CYP2R1 and CYP27B1 influence vitamin D activation. GC gene variants affect transport in the bloodstream, reducing availability for bone and immune function.Vitamin B12 transport & absorption (TCN2, FUT2):

TCN2 variants can impair transport of B12 to cells. FUT2 variants increase risk of B12 deficiency, particularly in individuals with limited dietary intake or absorption challenges.Vitamin A conversion (BCMO1 polymorphisms):

BCMO1 variants reduce the efficiency of converting beta-carotene into vitamin A, potentially impacting eye health and immune function.Vitamin K recycling (VKORC1 variants):

VKORC1 variants can disrupt the recycling of vitamin K, increasing dietary requirements to maintain bone and cardiovascular health.

Mechanisms of Genetic Impact

Altered enzyme efficiency:

Reduced activity of key enzymes, such as MTHFR, limits activation of vitamins and contributes to nutrient imbalances.Transport and binding protein variations:

Variants in transport proteins (e.g., GC for vitamin D, TCN2 for B12) can reduce delivery of vitamins to target tissues.Epigenetic regulation and methylation pathways:

Genetic variants, combined with vitamin deficiencies (e.g., folate, B12), can impair methylation processes essential for cellular repair and overall metabolic balance.

Genetic Variants and Their Impact

Gene | Vitamin | Functional Impact | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

MTHFR | Folate | Reduced enzyme efficiency; slower methylation | Higher risk of fatigue, neurocognitive issues |

VDR | Vitamin D | Lower receptor sensitivity | Decreased vitamin D activity; weaker bone health |

TCN2 | Vitamin B12 | Impaired transport to cells | Potential B12 deficiency; low energy levels |

BCMO1 | Vitamin A | Reduced beta-carotene conversion | Increased risk of vision and immune health problems |

VKORC1 | Vitamin K | Impaired recycling; reduced utilization | Increased need for dietary vitamin K |

Dietary Vitamin Impact in a Genomic Context

Genetic variation strongly influences how vitamins are absorbed, metabolized, and utilized. Two individuals on the same diet may have very different outcomes depending on their genetic profile.

Why Standard RDAs Don’t Apply Universally

Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) are population-based guidelines that do not account for individual genetic differences. Variants in genes such as MTHFR may reduce the ability to process standard folate, requiring the methylated form instead.

Additional factors further complicate nutrient status:

Gut microbiota composition affects nutrient extraction and varies significantly between individuals.

Nutrient-nutrient competition, such as calcium and magnesium competing for absorption, can reduce bioavailability.

Nutrient-drug interactions can impair absorption and metabolism.

Evidence-Based Dietary Strategies

Folate & B-Vitamins:

Patients with MTHFR variants benefit from methylated folate. Those with FUT2 or TCN2 variants may require active forms of B12 to prevent deficiencies.Vitamin D:

Variants in CYP2R1 and VDR influence vitamin D activation and utilization. Personalized dosing guided by genetic data and monitoring of serum 25(OH)D levels is recommended.Fat-Soluble Vitamins (A, E, K):

BCMO1 variants reduce conversion of beta-carotene to vitamin A, making preformed vitamin A more effective in some patients.

VKORC1 variants affect vitamin K recycling, requiring closer monitoring of intake for optimal blood clotting and cardiovascular health.

By tapping into nutrition genomics vitamins, you’re providing more than just dietary tweaks, you’re delivering clarity and precision to a world where guesswork just doesn’t cut it.

Clinical Application: Translating Nutrition Genomics into Practice

Integrating nutrition genomics into patient care requires structured steps: reliable testing, informed interpretation, and targeted interventions. This approach enables practitioners to address vitamin metabolism issues with precision and measurable outcomes.

1. Selecting Appropriate Genetics Tests

Choose validated SNP panels that focus on key genes involved in vitamin metabolism, such as MTHFR (folate processing), VDR (vitamin D receptor), and TCN2 (vitamin B12 transport).

Prioritize labs that provide practitioner-oriented reports, which highlight both genetic variants and associated risks for nutrient deficiencies.

Avoid direct-to-consumer testing services that offer broad results without clinical context, as they often generate confusion and require additional practitioner time to clarify.

2: Integrating Genetics with Clinical Markers

Once you’ve got the genetic data, the real work begins. Understanding when to tweak dietary

Genetic data alone is insufficient for treatment planning. Pair it with laboratory measures to validate and prioritize interventions:

Homocysteine and MMA for folate and B12 function.

Serum 25(OH)D for vitamin D status.

Other nutrient-specific markers depending on patient history and clinical presentation.

For example:

Patients with MTHFR variants may benefit from methylated folate rather than standard folic acid.

Those with CYP2R1-related vitamin D issues may respond best to targeted supplementation rather than relying on sun exposure alone.

3. Designing Targeted Interventions with Long Term Follow-Up

Effective interventions combine precision supplementation and dietary adjustments:

Use active nutrient forms where genetic variants impair metabolism (e.g., methylcobalamin for B12).

Adjust dietary sources to match genetic capacity (e.g., preformed vitamin A for patients with BCMO1 variants).

Ongoing assessment ensures interventions remain effective:

Re-test nutrient biomarkers periodically to track progress.

Encourage patients to record diet, energy, mood, and symptoms to identify improvements or new challenges.

Adjust protocols as needed to maintain alignment with genetic predispositions and evolving health needs.

By integrating genetic testing, pharmacogenomics, smart interpretation, and tailored interventions into your practice, you’re not just playing a guessing game, you’re giving your patients a customized roadmap to better health.

Practitioner Takeaways: Advance Your Skills in Nutrigenomics

Nutrigenomics offers practitioners the opportunity to move beyond generic recommendations and truly individualize patient care. By understanding how genetic variations shape vitamin metabolism, you can design targeted interventions that improve absorption, utilization, and long-term outcomes. Genetic testing, combined with careful interpretation, transforms nutrition from trial-and-error into a precise, preventive strategy that supports sustained wellness.

For those looking to deepen their expertise in this field, the Integrative Genomics Specialist Program by Elite Gene Labs equips clinicians with the tools and confidence to interpret genetic data, connect it to key health pathways, and create actionable care plans. With expert guidance, practical resources, and a recognized credential, the program positions you to lead in the future of personalized nutrition and integrative care.

Personalized nutrition is no longer aspirational, it’s here, and it’s reshaping clinical practice. By investing in the science of nutrigenomics and advancing your skills through specialized training, you can offer patients clarity, precision, and outcomes that truly reflect their biology.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is vitamin metabolism nutrigenomics, and why does it matter?

Vitamin metabolism nutrigenomics explores how genetic differences influence the way your body absorbs, processes, and uses vitamins. This science helps explain why two people can eat the same foods yet have very different nutritional outcomes. Understanding these differences enables tailored dietary recommendations based on individual DNA insights.

Which vitamins are most affected by genetics, according to current research?

Genes commonly linked to vitamin metabolism include variants in MTHFR (folate), VDR and CYP2R1 (vitamin D), BCMO1 (vitamin A), VKORC1 (vitamin K), and CYP4F2 (vitamins E and K). These changes can influence absorption, activation, and nutrient utilization in the body.

How can genetic differences impact standard nutrient recommendations?

Standard RDAs are population averages and don’t account for individual genetic differences. For example, those with MTHFR variants may need methylated folate rather than standard folic acid. Similarly, CYP2R1 variants can affect vitamin D conversion, making standard dosing insufficient.

How does genetics influence vitamin D metabolism and absorption?

Variations in CYP2R1, a key enzyme in activating vitamin D and in VDR, its receptor, can significantly affect vitamin D status. People with lower CYP2R1 activity may struggle to produce sufficient 25(OH)D, even with supplementation.

Can vitamin metabolism nutrigenomics help prevent nutrient-related health issues?

Yes. Genetic insights into vitamin metabolism can help practitioners create precise dietary and supplement plans that prevent deficiencies and reduce risks of chronic conditions like metabolic syndrome, by optimizing nutrient status for each individual.

How does Elite Gene Labs support personalized nutrition for practitioners?

Elite Gene Labs offers training and tools to help healthcare professionals interpret genetic variants affecting vitamin metabolism and apply that knowledge in clinical care. Their programs help bridge the gap between genetic insight and practical nutrition planning.

What are common confusions about nutrigenomics and vitamin metabolism?

A frequent misunderstanding is believing that having a genetic variant is a diagnosis. It’s not. It’s a guide. Effectiveness comes from combining genetic results with lab data, clinical signs, and consistent monitoring to tailor nutrition to actual needs.

References:

Bösch, E. S., et al. (2025). Vitamin metabolism and its dependency on genetic variations among healthy adults: A systematic review for precision nutrition strategies. Nutrients, 17(2), Article 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020242

Al-Batayneh, K. M., Al-Smadi, M., Alzoubi, K. H., Khabour, O. F., & Khader, Y. S. (2018). Association between MTHFR 677C>T polymorphism and vitamin B12 deficiency: A case-control study. Journal of Medical Biochemistry, 37(2), 141-147. https://doi.org/10.1515/jomb-2017-0051

Duan, L., Xue, Z., Ji, H., Zhang, X., & Zhao, Y. (2018). Effects of CYP2R1 gene variants on vitamin D levels and status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gene, 678, 361-369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2018.08.056

Matteini, A. M., Walston, J. D., Fallin, M. D., Bandeen-Roche, K., Kao, W. H. L., Semba, R. D., . . . Arking, D. E. (2010). Transcobalamin-II variants, decreased vitamin B12 availability and increased risk of frailty. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 14(1), 73-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-010-0013-1

Doğan, D., et al. (2023). Genetic influence on urinary vitamin D binding protein excretion and serum levels: A focus on rs4588 C>A polymorphism in the GC gene. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14, Article 1281112. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1281112

Dutta, S., et al. (2011). Importance of gene variants and co-factors of folate metabolic pathway in the etiology of idiopathic intellectual disability. Nutritional Neuroscience, 14(5), 202-209. https://doi.org/10.1179/1476830511Y.0000000016

Bailey, R., Cooper, J. D., Zeitels, L., Smyth, D. J., Yang, J. H. M., Walker, N. M., . . . Todd, J. A. (2007). Association of the vitamin D metabolism gene CYP27B1 with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes, 56(10), 2616-2621. https://doi.org/10.2337/db07-0652